- Home

- Paul Mendez

Rainbow Milk Page 2

Rainbow Milk Read online

Page 2

The next year, Jamaica lick by a hurricane that can only come from the bottom of the Lord own belly. We don’t suffer to that, for Daddy was a builder and he construct his house well, but the island mash up bad. The wind tear out the whole crop. The coconut, banana, pimento and sugar cane all kill off for five year at least. Bird, bee and butterfly lose their home and each other. Overnight everybody job finish. I did work in the sugar cane field every summer since I turn fourteen, to help my mother dressmaking money. The bauxite mine not open yet, and the American shut off the seasonal work opportunity that the Jamaican always use to have. My second brother Ellery take over Daddy business, so I help him a lot with all the work that need to be done after the hurricane.

I tell Mr. Chambers about the hotel, and how they clear it all out to build a ballroom and car park.

“That ghastly Lomax,” he say. “These wealthy Americans I’m afraid have an appalling taste for the vulgar, and I dread to think what’ll happen the more of this planet they colonise.”

But then I sip the tea, and it don’t taste right. I look up at Mr. Chambers, and he haven’t sip it yet. He mix up the tea with milk and sugar, then leave it on the table in front of his knee. It then I realise that the milk sour. Can happen in this heat. But he can hear Mommy footstep creep back to see how we be, and quick as you like Mr. Chambers throw the tea in the plant by his armchair and smile on her so bright and handsome she don’t notice the steam rise up from the soil.

“It was me or the dracaena palm, dear,” he say to me some time later. “But that coconut cake was divine, so soft and subtly sweet. I haven’t been able to quite stop thinking about it. Do you think Mrs. Alonso might be prevailed upon to share her recipe?”

I think to myself, if we give you the recipe, who will make it? We don’t give away recipe like that in Jamaica. They get pass down from mother to daughter to granddaughter. Women don’t teach their son to cook, and they are too competitive to let anybody outside the family know their flavour secret. They did rather their son come trouble her for food every night than give their daughter-in-law their mix. Every christening, wedding, big birthday and funeral every one of the mother will bring her own pot of food and watch how quick it empty down till people scrape the bottom. Everything Mrs. Alonso cook done first, every time. One time I see a big man pick up the whole dutchpot to lick out the bottom till the gravy all over his chin, which he wipe with his sleeve, then suck the juice out the sleeve! That how good is Mommy cooking. My three sister all beautiful and sweet but their husband did marry them up quick because them want to eat my mother cowfoot soup and Sunday mutton. She won’t give it away.

* * *

—

“Daddy, I finish.”

“Good boy. Clean up everything now. Make sure nothing left on the table or on the chair. You have crumb on your shirt?”

* * *

—

Mr. Chambers have one housekeeper, Mrs. Dinkley, who cook all his food, mostly what he must eat in England: egg and fruit for breakfast, soup for lunch and a chicken dinner, might be. She won’t go out her way to change his taste, or season or spice up his food to that. He never ask for Jamaican food, which Mrs. Dinkley can cook as good as any woman who is not name Mrs. Naomi Alonso. But God help the man who can go behind the Jamaican lady in his life back to ask for another woman recipe! Woy! Mrs. Dinkley a hard-face woman. It take must be six month after I start work at Weymouth House before she even say Hello to me. As far as she concern, I’m just a field hand with big muscle and no mind. I think it would take a thousand year before Mommy let she know any of her recipe. But as soon as I get home that afternoon and mention that Mr. Chambers did inquire about her toto, my mother chase a pickney to run bring her money box from her bedside table. “Make haste, come quick before it close!” she say, and send me out to buy the best paper I can find. I get to the post office in St. Ann’s Bay. Mr. Jeffrie step out from behind his counter to shake my hand and ask me what can I do for you, Mr. Alonso? He must hear that I get hire by Mr. Chambers, so I am almost like a gentleman myself, even as I stand there in Daddy old boot. Mr. Jeffrie smile on me for the first time in my life—even though my mother did send me to the post office at least once a week since I was a child—and wrap up the paper good in a little red bow. Just as I am about to hand over the money, he ask me if he should charge it to Mr. Chambers’s account!

“Which part you get this paper from?” Mommy say when I reach back with it, holding it up to the light out the front porch. “Might be the ink won’t even write on it!”

“It’s fine paper, eh?”

“And why you come back with the money? Boy, I don’t raise thief!”

“Mr. Jeffrie ask me if I should put it on Mr. Chambers’s account.”

She gasp like I cuss in her face, and whisper-shout: “Suppose he find out and sack you! Why you want to lose another job for!”

“Well, Mr. Chambers ask me for the recipe, and he must know that we want to give him the best, or else why you sit him down in the front room chair and give him the nice china for tea, which he said was better than in England, by the way.”

There is nothing that Mommy love more than flattery. Since Daddy dead she don’t bother with herself, but after Mr. Chambers show up unannounce she pin up her hair and wear small-heel shoe every day, in case he choose to stop by again. All her grandchildren them get their hair comb and oil every day, and they dress up and sit quiet like for photograph. The whole house make up like the front room.

“Just think how happy he will be when he see the recipe for your toto on beautiful paper like this,” I say to her, and I can see the little cog in her mind tick around. “He will keep it forever, and when he die, they will find it and put it in a museum in London. Your recipe a go famous through all the world!”

She look me up and down.

“Ee-eeh? A so you stay, now? Which part you learn to talk like politician? Everything on Lord Chambers’s expense? Mm-mmh! Norman nuh easy! You can write good? Come in your Daddy study and write down the recipe. Lord God me never see paper so thick in all my life. Sit down at the desk. Your hand clean? Nuh bother splash the ink all about. Take time with the pen.”

First she make me sit in the settee, now she let me sit at Daddy writing desk. I don’t think this room open except by my brother Ellery to look for one or two paper, or by Mommy to dust around a little bit and water the plant, since Daddy dead two year before. I look up at all the picture on the wall. Mommy and Daddy, smiling, Daddy tall, brown and handsome with his moustache, Mommy still beautiful and elegant in her white glove and pearl earring. My two brother Philip and Ellery, my three sister Loretta, Marlene and Delfi, and me, the youngest by six year, all as baby, all in we little white gown. Woman seem to live long time but man just work and work till them dead. Granddad dead. Daddy dead. Philip dead. Nan strong. Mommy strong. And I sit and wait for Mommy, with the nib in my hand ready to dip in the inkwell, at Daddy desk, in his chair, with the precious paper beneath me, but she don’t know what kind of oven he have, she don’t know which kind of dish he will cook with, so she don’t know which amount to tell him, and she don’t measure anything out even once in her life because she just know, she just take the right amount every single time, mix it up, pour it into a tin and bake it in the oven until it nice and brown. Then she take it out, make it rest a little while and cut a piece for everybody who want it warm, then put what is left on a platter under a cloth with a little drip of water on it so that it don’t dry out. That toto never last more than one or two day because it eat so nice and people come round to eat it because the baking smell like heaven when they pass by we house.

I see that she have a little tear in her eye, because Mommy realise she can’t write down a recipe for Mr. Chambers. She can’t give it away like that. Not to that ugly black-face Mrs. Dinkley, she say, and we laugh.

“Put down the pen and come,” she say. “I will show yo

u how to make it for him.”

My little niece Andrea and me get teach the same time, just like my grandmother would one day have shown my mother when she did ten or eleven. And now I think, my mother don’t have any daughter left to give away to good man, and Andrea still too young. But she do have a son, twenty-six year old, tall, strong and hard-working. Every minute my mother ask me, “But why such a handsome, tall, nice, rich Englishman don’t have wife? What he is doing up there all by himself in such a big house with all them flower and no woman fe give them to? All he have is that black-face Dinkley woman and my Norman. How old is he, you think? He don’t even have son fe leave it all to?” She put everything in place, but never look to put two and two together in her mind. Instead, she send me with the toto I bake when I go to work for him the next day. Mrs. Dinkley don’t say anything but she purse up her lip like fist and turn her eye away.

* * *

—

“Finish, Daddy.”

“You clean up good? If I stoop down my big self and find something on the floor me go take switch and beat you. That’s it. Climb down there and make sure the floor clean. If your mother come home from work and find mess she will beat you as well. Talk, child; I can’t see.”

“Finish.”

“Finish what?”

“Finish, Daddy.”

“You put them nuh your mouth or in the bin?”

I know exactly what he done but children always think they’re smarter than you. Especially Jamaican children. He think because I can’t see what he is doing properly that I have no sense of time or space.

“The bin?”

“But I nuh feel you walk round me to go to the bin in the pantry, which must mean either no crumb on the floor, and you lie, or you put the dutty crumb in your mouth, and you lie. Which one it is?”

“Me eat them,” him mumble.

“Speak up! What did you say?”

“Me eat them!”

“Don’t shout at me! You narsy, and a lie you a lie. Go in the garden carry switch come me guh beat you.”

“No! I’m sorry!”

“I say to don’t shout at me! What you sorry for? You sorry that you lie or that you eat the dutty crumb from the floor?”

“I’m sorry…fe eat…and nuh put it in the bin…and fe liiiie,” he cry.

“Say you sorry to Daddy, Mommy and Glorie that you lie and eat the dutty crumb off the floor!”

“I’m sorry, Daddy!” He turn to face the door and shout like his mommy will hear in the hospital: “I’m sorry, Mommy!” and then him turn gentle again to his sister on my lap. “I’m sorry, Glorie.”

“I tell you from long time now, you a big boy, and have to provide a good example to your sister so that she learn how to behave properly, you see?”

“Yes, Daddy.”

“You do the job me and Mommy ask you to do straight away and in the right way, a so me mean, and you don’t lie bout it, because when we find out, the consequence a go bad for you, you hear?”

“Oh, Daddy…”

“Stop the cry! Stand up! You want tea?”

“No.”

“No what?” This boy never a go forget his manners round me.

“No thank you, Daddy.”

“You want water?”

He don’t say anything, so either he shake or nod his head. We don’t yet get to the day that my child don’t answer me at all.

“I can’t see. You have to tell me.”

“Sasprilla.”

What a way this boy can lie and still feisty enough to ask for his favourite drink.

“You want sarsaparilla?”

“Yes please, Daddy.”

I can’t see his big eye upon me but I know all about them.

* * *

—

It was Claudette who insist we come to England. She want to get away from this nasty little island, she say, when I get a letter from my old schoolfriend Laury about how life so good in the Black Country. So much real man job I can try a hundred things before I settle on one, he say. Doreen and me will look to buy house. Claudette and I did court for must be six month; we marry, then we travel, then she find she pregnant with this little man. She love me, but she marry because she want to better herself. She dream that England like something out of one of the upper-class romance novel she love read. She say she want to give we children the education they can’t get in Jamaica, because we not rich enough. She think that all English children must get good education.

Mr. Chambers say Jamaica will gain independence while Harold Macmillan prime minister. They already give the Gold Coast it independence and call it Ghana. Ghana live a Englan’, I say, and it take him a little while to get the joke but he laugh. He tell me he will miss me, and that I must remember to write him. I miss him, too. He value my knowledge and skill as gardener. He don’t take exception when I tell him what to do, and it on his verandah that I drink little red wine from France for the first time and listen classical music record, great big Wagner and romantic Tchaikovsky. Sometime now when I work in my own garden and the children asleep I listen the Third Programme. I never, before him, see man dress with such refine taste, who speak in such elevated way. He give me book to read—The Great Gatsby and Of Mice and Men—and my mother send him currygoat, rice and gungo pea to eat. It him that make me expect everybody in England to be a fine gentleman.

Laury is my friend, but I know I should not trust somebody whose face make me happy to be blind.

It my beautiful son and daughter who make me miss my eye.

* * *

By the grace of God, Claudette and me, with two week and eight thousand mile gone, set we eye first time on the Mother Country, and what a wondrous sight we see. A bright cheer rise up as she appear true on the horizon, still far away on that warm, spring day. Already it seem like everything white; the bird in the air, the rock formation that stand up so like a baby first teeth. Claudette look beautiful in one nice blue dress with her best hat and glove. She smooth her hand down my lapel; only the gardenia did missing from my wedding outfit. We kiss, my hand on her belly, then round her waist. We baby will be born in England, in time for Christmas, in the snow. We never see snow, yet. I can’t wait. We will build snowman with we baby, in we garden, drink hot tea with rum and breathe the steam up in the air.

The ship did never quiet. Musician who never meet before the journey entertain we with mento song. Engineer trifle with nurse over pudding; single lady drinking tonic in hat and glove practise their finery front of mechanic and clerk; aunty going to look after their family sit in the corner and watch as if at a wedding, hoping a young man might ask them to dance, so the band play “Old Lady You Mash Me Toe” and everybody there laugh; skill work-hand talk about a couple years to make money then home, same time they sip rum and smash domino on the table; playful boxing contest make Claudette both mad and proud when girl whistle down my physique. We even play little cricket match on the deck with the back of an upturn chair for stump.

A great crowd of we walk down the gangplank at Southampton, the bawl of the bird and boom of the engine on the water replace by the hiss of train pull in and out, and the babel of we under the iron beam. We make friend on the boat, but we all have different address write on piece of paper in we pocket, so we embrace, wish luck and depart, some of we for London, others for Liverpool, others, like Claudette and me, for Birmingham. We wait at custom and show we paper and passport, and the man, who don’t smile, tell us to catch a train to Paddington then change; the Birmingham line is closed for now. A man threw himself in front of a train, he say. Claudette gasp: Is he dead? and the man say, I should think so, but we know that just as bad things happen in Jamaica, so we get it out of we mind with the excitement of going on the train.

It was the twenty-sixth of May, ’56, and it really did feel like we start a new life, inside Claudette belly and

outside, beneath the English sky, where fluffy little English cloud pass overhead, slow and gentle. I watch my wife looking out of the window, and think, she not Jamaican again, because she English now, a beautiful brown Englishwoman with sexy red lip I love to kiss. The mother of my English child. I look forward to my new house and garden, and I already start think about the rose, dahlia, jasmine, hibiscus, pear and lemon I will cultivate, and we look forward to move in with Laury and Doreen in a town call Bilston in the Black Country, and meet we new neighbour, cook Jamaican food, and them for we, English food, as we wind in and out of each other house like family, we children and their children playing together and learning together, growing together, black children and white children the same way. We children will learn to speak good like real English people, get good education, grow up good and not have to work in factory or in the hospital, for they will have better opportunity than we, to become teacher or engineer or real nurse, and meantime I would get job in factory or on railway just to settle we, and then I would work another couple year until I can afford start my own gardening business, for plenty rich people in England will be too busy or grand to look after their own.

We get off at Paddington—an iron cathedral—and can’t believe we standing in London, breathing London air, watching London people walk by with their black suit, newspaper and briefcase. Claudette learn more about fashion in one minute looking all about at woman walking by than she did reading those magazines she used to steal from the hotel lobby. We think about going to visit the Queen, but we don’t want to miss we train; we feel like we might get lost if we do. We don’t know where to go, and we never see so many people in one place in all we life, so we have to be careful not to get separate and lose we luggage as people come up around us from every direction, almost knocking Claudette out of their way as she point that way and I point the other way—they don’t care that she pregnant!—and bouncing off me, kissing their teeth as they run toward their platform. I don’t know how many times we say Sorry! Sorry! Sorry! We ask an attendant, in a hat, who speak to us polite like we live there already, and he point us in the right direction. On the way is a florist truck, and I quickly pick up a bunch of pink rose for my sweetheart (first time me count out sterling to pay for something; I can’t forget the jealous look on Mr. Jeffries’s face when me draw it out). She feel even more glamorous when a photographer man stop we and ask to take we picture. Dizzy, we walk down the platform to second class, past all the rich white people like government official in the first class carriage, and a porter take we luggage.

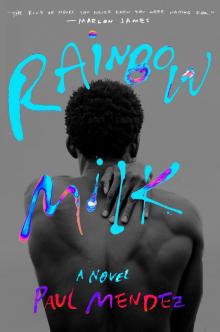

Rainbow Milk

Rainbow Milk