- Home

- Paul Mendez

Rainbow Milk Page 4

Rainbow Milk Read online

Page 4

So next time Maurice want to go for a drink, I go with him to the Black Swan, me, big like Goliath, fist like brick, and we walk right in to the saloon bar, him first, then me, and I feel their face change, I feel their back freeze up like cat. They stop playing snooker; the thud of the next dart take long time to come. The dog hide under the table and flick their tail. Tall as the gas tank in my grey suit, I walk up to the bar and we stand there, wait, and wait, while the bartender serve some man who come up after we, wash some glass, scratch his ball and wipe down the bar. Mar twelve-year-old’s gerrin a trial at the Albion / Tell im not to gerris opes up too much, he’ll always a’the gas works. / Burry woe know if he doe troy though, will he? What’s he got to lose? / Even Duncan Edwards trained to be a carpenter, day ’e. / Ar, and look wharrappened to im. / Terrible ay it. Rest in peace. But we wait, quiet and patient, we breathe; we don’t get frustrate, and I hold Maurice hand when I hear the jingle of his bracelet. It look like the bartender—a fat, round man with must be about three chin, his trouser pull up right underneath his chest, tie up with must be a three-yard-long belt—need to clean up his bar, fix up himself and take time to serve we, because we are Black gentlemen, this pub call the Black Swan, and this region call the Black Country.

Finally he nod to we, say, next please like he don’t know. I look in his eye and smile and say, good evening, sir, and he say back to we, good evening but he don’t smile. It seem like he did step up to we with cosh at his back, but I turn to Maurice and ask him what he want, and he say he want a beer. I say, that is an excellent idea, Maurice, and Maurice look at me funny under his pork pie hat, but I turn to the bartender and ask for two of his finest pint of beer please, bartender, and the bartender say, Two pints of beer it is, but he still don’t smile. He take two glass, put down one then take the other one, pull the lever until the glass full, and place it down nice on one mat in front of Maurice. Then he take the other one, pull the lever until the glass full and place it careful on the mat in front of me. I watch every step—because I can still see good, then—to be certain he don’t spit on my beer or perpetrate some other nastiness against black man in his pub, and he don’t spill even one drop, not even one drop of anything but condensation did roll down the side of my glass. He stand back and say, One and fourpence please. I put my hand in my pocket and again his batty muscle tight up like I might pull machete out on him, but I keep smiling, hold my hand up to my face, count out the correct money and drop it in his hand. He take away his hand quick as I drop the coin so that he don’t get touch by my dirty jungle finger, but I don’t care about what he say and do, because then I turn to Maurice, smile on him and tell him in fast patois the bartender won’t understand, a so yuh reach a pub n’a country yuh nuh baan. “God bless you, sir!” I take a big long gulp at the bar and make sure everybody in the saloon can hear how refreshing it feel: Ahhhhhhhh!

We laugh and drink we pint, then drink another one then leave, because I can’t take the smell of the pickle onion.

* * *

February ’58, Claudette start to feel pregnant again; we don’t plan for another baby but we don’t not try. We deep in bed asleep when we startle up by crashin’ sound. Robert wake and Claudette scream. I take the cricket bat from under the bed and run downstairs. I find the curtain blow in from the street. I turn on the front room light and the carpet cover in shatter glass, and in the middle, a brick wrap up in paper. I tell Claudette to shut up and call the police. They come round must be fifteen minute later. They ask me if I have trouble with somebody recently, and I say no. But then they start to search up the place, and they ask me what I do with all these sign cheque write by Councillor Clifford Parker in my house, and I tell them I don’t know anything about them, and now Claudette screaming again, because they arrest me and lead me off to the police station. They leave we door open with one officer there. All the neighbour come out of their house to watch me arrest, and it take a long time to make them all know that I did nothing wrong.

* * *

—

“Take that,” Robert say, and the Indian must dead in the fireplace.

“A good job the fire not on,” I warn him.

* * *

—

The forge cheque must plant there, because I never see them yet, and not because my eyesight spoil. I tell them to call Mr. Parker. They wait until morning, then Clifford himself come to the police station to vouch for me and convince them not to prosecute. It plain to me, for I read plenty Sherlock Holmes and Edgar Allan Poe story back home, that it Teddy Boy Peter who organise it. Maybe he have a friend in the police who he give the cheque to plant in my house because I am just a big nigger who nobody will believe, and he can punish me easy like that because he is too idle and he lose his job. We can’t have brick fly through we window every night. We don’t have relative to stay with. We thirty and twenty-three. It is me one who have to take care of my pregnant wife and son, and I can’t have my life control by some mash-up white idiot like Peter. If people are jealous of my friendship with Clifford, I decide to finish it.

I thank him and tell him I can’t work for him again if it put my wife and son in danger. He disappoint but he accept my resignation, and send the council to come fix up we house. When he drop me home, he tell me to call him whenever I need anything. Anything, he say, and squeeze my leg.

It can’t do me good to rely on people who don’t know how to handle me. They put you front a themself and control you like game. I apply for the same kind of job but nobody want to know; again, they all say the vacancy fill when they hear my West Indian accent. I realise I did lucky to get through to Clifford, but I know I’m too proud to turn back. After two week of unemployment I take a job at the gas works, shovelling coal in the retort to burn at a thousand degree, surround by young man like Peter and old man who do the same job all them life. That is the life I can handle, if I can keep to my own business. We have we own garden to make beautiful. I remember the flower truck at Paddington station and think, maybe, if we good with we money, one day we can set up we own flower truck, Claudette and me, and send we children to a good school.

* * *

—

“Take that!” Robert say again.

“Robert, gimme them.”

He must think I wan’ play with him, because he gimme them straight away. I take them in the kitchen an’ put them in the bin. I come back in the front room and sit down. Seem like he a try to get up to find them.

“Sit down. I don’t play game with you.”

“What happen?” he say. His voice sound like panic.

“I put them away. Plenty other toy you have,” I say.

He don’t know what I mean. He start to cry. I pick him up and cuddle him. I forget sometime he just two.

“Shut up cry and listen. When you a play with cowboy a’Indian, you a take the role of the white man and kill the brown man, when in real life, you not the white man, you the brown man, and the white man want kill you. A so me mean. You haffi learn that.”

At no point should my need come before that of a white man, so man like Teddy Boy Peter think. Clifford a good friend, but when he not by my side, how I can walk in his world? I am too big, too black. My boy scream to learn that there lesson.

* * *

Soon as I start at the gas work it make me wonder why I bother move to England at all if this my level. I also start to wonder whether, if God did ask me which way I did want to fall down, I would choose to be blind or hard-of-hearing. The shit I hear talk every day make me think I did sooner go without ear than eye. Without ear, I can still see Claudette and my children and read book but I don’t have to listen the workmate language, if I can call it that.

I don’t know this about England when I did back in Jamaica, but they have this whole spread, thick like lard pon bread, of people who can’t read, can’t talk good, scratch themselves up like dog with flea, don’t understand a thing a

bout life outside their own head, but think they can call me nigger, darkie, coon, gorilla, tell me to go back to my own country where I belong and stop steal their sunlight—I don’t have enough back in the jungle? I don’t melt, like chocolate? The ignorance, the way they talk about their missus like she a bucket with hole, or they can’t talk about anything more than which football team better, Albion, Villa, City or Wolves.

Seven, eight month I did keep my cool and fasten up my mouth among these men. They chase me and I walk away, head down. It feel like everything happening same time. The football World Cup, and the first black man I ever see who better than every white man, just like Jesse Owens with the Nazi. The workmate start to talk nice and tell me I’m good-looking and should model underpant in the catalogue or box professional, and they ask me why I don’t join their boxing syndicate, because I could make some money out of it. I ask back how much and they say ten per cent of the takings go to the winner. I kiss my teeth and shake my head, and then they take a different turn, because they can never understand, never mind that it none of their business, how I did walk good and talk good, as if I should be making inarticulate sound and dragging my knuckle along the ground; they want to know how I sometime can use word they never hear, because I read, and most of them did go to school but, as Mommy would say, they nuh go fe learn, they go fe rude, and they think because we all work in the same industry, that we must all have the same mind. They don’t like it that me, a black man, can think I am better than them, even if I can’t say that I am better than them. It seem I can’t go anywhere and not be an outsider. Too black for the council and too educated for the gas work. Any man can shovel up coal and feed retort. Not everybody can be Norman Alonso.

What the workmate can’t understand, is that I am a Jamaican. I am a Jamaican man, and therefore, a British man. I did born British, so will be a British man all my life. We serve the Queen, and before her, the King, in the same way. Any time you walk down the main street in downtown Kingston you can hear one marching band play “God Save the Queen.” We fight for we country. We help build this country. We help make rich this country. Without we, they might not have such a big army, such a big navy. They might not have been able to conquer the world. Might be they did lose the war against Hitler.

The littlest one, McCarthy, with his curly hair and boy-face that still look rude from school, come up to my chest and tip his head back like Claudette do when she want a kiss, and ask me what black woman cunt taste like because he imagine it like gravy, and what my wife like best for dinner, and I tell him, slow and deliberate, to remove himself up from out of my face before I crush him down, and some other man come up and tell me, Leave him alone. He’s just yampy, but I say if he is ignorant then like we say in Jamaica, If you cyah hear you mus’ feel, and all of a sudden I am surrounded, and my blur eye can’t see everything, but I push McCarthy little way from me because his mouth stink, and next thing one other man step in front of him and throw punch. I take one step back and kick him out my face, and his eye don’t leave mine as he fly back and skittle down the two man behind. McCarthy scream to lose his tooth. The workmate stop and back away. I stand there midst of them like hand grenade with the pin about to pull out.

You can’t blame them. Colliery. Ironwork. Brickwork. Chainmaking. Work with their back and their arm, and not their brain. Metal is the work of their hand and the material of their mind. What produce grease and black smoke is good. That the history of this part of the country. Skilled labour. Their father did the same and their grandfather and great-grandfather before them. They work all day every day, go home to pie, mash, gravy and peas, then take their retirement in one of the English pub. There is a typical kind of man in the corner every afternoon, waiting to die, with no teeth, smoking cigarette after cigarette, drinking pint after pint, going to the toilet every twenty minute, too thin, his pale yellow skin drooping off his skeleton, his eye sunk back in his head, his white hair slick back, the same clothes he did wear when he was thirty hanging off his bones and secure with a belt.

The government don’t talk to poor white people, just in case they give them too much information. Nobody tell them that immigrant come because the government invite we as free British citizen, because after the war so much get knock down to rubble and so many man get kill. They think we come in to get free money from their system and take over their livelihood, and put we own woman on street corner same time for make the little extra we need to buy we house. The establishment afraid we might take their perfect English landscape and strip it down to bush and savannah, exchange all their cow for goat and coal for sand. They fear we black people might run up in the parliament with spear and hand to we mouth, throw Macmillan on fire with English apple in his teeth, and take the Queen money to pay back the West Indian? They fear we might rape them dry like they did rape we for century, except we king cocky bigger than for their struggle cocky? Poor white people don’t get the right information, because the establishment afraid they might join we. Because they are ignorant, they take out their frustration and unfulfilment on peaceful, willing immigrant like Claudette, me and the rest of we from the West Indies. All of we work hard, all of we face persecution. They can’t understand that they get forsake just like we get forsake, that we both get raised by downtrodden mother and neglectful father.

* * *

I work hard, day in day out, sometime half-day Saturday, then Glorie born in September, same birthday as Claudette mother, and we name her after my grandmother. Claudette say she favour me with the eyebrow and her with the lip. Straight away she ask me why I hold Glorie face up to mine so close, but I have to study her face because my eye blurry and cloudy. Claudette worry that her husband losing his sight and that she might have to go out to look for job. She tell me, Go to the doctor go to the doctor go to the doctor but I don’t take the time off work. She start to think about all the relative she can send for from back home to come and help we.

Few days pass and nobody say anything to me at the work. The coal come in by rail. We pulverise and blend the coal and feed it into the retort, where it heat it up for thirteen hour at a thousand degree, which make coke residue. Sometime we poke the retort with long rod to quench the coke. Then we pump the gas through a purifier, full of wood shavings to soak up the impurity. It also make ammonium sulphate, to use as fertiliser, and water gas. Every five and a half minute you get a blow-off that show that a certain amount of gas been made. It all very clever. Tar, mothball also produce. The coke then quench in the water tower. The steam everywhere. The steam from the train, the smoke from the coal burning. Fifty hour I do this job, handle the machine, some day shift some night. It dirty and loud but I love it. In it ugliness it beautiful. A different kind of heat than Jamaica.

That was when the headache really start to get worse and worse, while we watch on the news all the Teddy Boy running up and down terrorising the black people in Notting Hill. I find Peter sneer in the face of every man and woman there; the hatred, the feistiness, the badmindedness, just like the little blond boy in Bilston. McCarthy turn out alright; he did just an ignorant man goaded by ignorant man. I’m sorry that I lose my temper with him.

Talk turn to the upcoming boxing tournament. One of the foreman, Grime, take time come up to me gently to tell me I always remind him of Joe Louis, that I have great reaction and strength and can make a lot of money as a fighter. I did see him around sometime but he never talk to me yet. In his pleasant, quiet voice, he ask me if I ever did box bare-knuckle and I say yes, in Jamaica from must be about fourteen to nineteen, when Lynval born and I start to work full-time as a gardener. I never lose. I did amateur champion in the district. Some of the promoter want me to turn professional but my mother say no, and even if I did old enough to take my own decision by then I know that she did right; she say me too soft and peaceful even if big. Ten years pass and my life not different from then. I still have woman to look after and children to raise, and we live in a country where

everything you don’t want cheap and everything you do want dear.

I tell him I’m out of condition and too old to start learn to box again like adolescent. It’s like riding a bike, Grime say. He even offer to train me himself. It don’t matter how many hour I put in at the gas work; the money did less than the council, and Claudette go from celebration to botheration when I give it up, for she host tea party in pretty dress in we garden and tell one jealous friend, Look how my Norman a march inna this country not even two year yet and already get a job for life and the friendship of a government official. Where for your husband, deh? Pon building site or sweep road or what? and she even write boasty letter to her mother about how her son-in-law she never like—because I am seven years older than her daughter with two son already—make a success of we in England, and now she is planning to set up a business to help West Indian immigrant find good job and fair accommodation when they come, only for me to spend less than two year in that job, and the friend that come by the tea party walk past we window to see we curtain blow inside because somebody throw a brick through it, that we were lucky was not a burning bottle. I think that this could be the way to make me favour in her eye again, if I can come home as boxing champion, with the winnings.

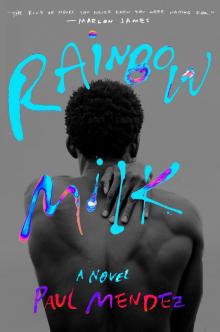

Rainbow Milk

Rainbow Milk